045

FOUR

“Monica, you must understand that this partnership agreement

was written forty years ago. It clearly states that you and Ernst

are equal partners, and there's no buyout provision. You'Ll have

to negotiate a settlement with him, that is, if he’s interested. In

any event you most certainly cannot just fire him.”

“Mein Gott!” shouted Monica, slamming down the phone. No

attorney was going to tell Monica Tietze, the cofounder of

Kuchen Kitchens International, what she could and could not

do with Ernst Gude. She would do with Ernst Gude what she

wanted, when she wanted, and as often as she wanted. After all,

that’s precisely what she had done since she was 16 years old.

Forty years ago. in Hamburg. Germany, Monica and Ernst had

been teenage sweethearts. He had a natural talent for baking

that everyone in the neighborhood knew about. In a country

where virtually every' other corner was filled with a bakery

store, Ernst’s apfclkuchen, sachcr torts, and streusel were

prized by the locals. Every evening he would prepare the sweet

delicacies that Monica would sell door-to-door. By the time they

were old enough to attend the University, Ernst and Monica had

a thriving business along with a respectable savings account.

Then they had to make a decision: Should they open their own

bakery shop, competing head-on with the several hundred

shops already in the city, temporarily shut down the business

and attend the University, or ... ?

Monica had always wanted to live m the United States, the land

of opportunity. Thanks to persistent urging on her part, Ernst

finally agreed to move overseas for one year—just long enough

to discover whether or not they could duplicate their

hometown success in America.

Four decades later Kuchen Kitchens International had grown

into a worldwide franchise of bakery shops, including two in

Hamburg, and a chain of catering outlets with locations in every

major metropolitan city of the United States. Unfortunately, the

demands of a thriving business had caused Monica and Ernst’s

romantic relationship to fall by the wayside.

Midwife to the firm's prosperity, Monica oversaw every aspect

of the business, save one. The recipes. Those were Ernst’s

domain. Having expanded his culinary capabilities into gourmet

cuisine, he spent most of every day in his personal test kitchen.

Located adjacent to his office suite, Ernst’s test kitchen was

coveted by everyone who saw it. Monica had paid special

attention to the kitchen’s design, even accenting it with a wall

of floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the harbor, simply

because that’s where she wanted her partner to stay—in the

kitchen and out of the business.

Nonetheless, roughly once a quarter she had to put out a fire

Ernst would start in any one of the seven countries where the

firm did business. He’d interrupt contract negotiations with a

new franchisee in Belgium, order double inventories tor a

catering warehouse in Japan, halt construction on a new site in

France, or, on a really bad day—call an emergency staff meeting

just to discuss a new letterhead. Monica had quietly resorted to

sending him on trips to research new recipes, while constantly

outfitting his kitchen with an ever-changing array of new and

expensive gadgets. As far as Monica was concerned, what had

begun as bothersome interferences had turned into full-blown

catastrophes. And what had begun as mutual love and

admiration had finally turned into full-blown distrust and flat-out

hatred.

This last go-around, the call from their friend and client Yolanda

Baccus, the head of purchasing lor Fairweather & Company,

put Monica firmly over the edge. According to Yolanda, Ernst

had offered to personally oversee altering for the groundbreaking

ceremonies of Fairweather’s new offices in Smithfield, but her

guests were due in 45 minutes, there were no food trucks in

sight, and she couldn't get ahold of him.

In quick succession, Monica made three phone calls. She

reached the manager of the Kuchen Kitchen Kateri ng outlet in

Smithfield, who had never heard of Ms. Baccus but did have

plenty of food and cakes on hand for her groundbreaking

ceremony. He and his staff were commanded into action. Next,

she called Yolanda back, apologized profusely, told her that a

choice selection of delicious items was on its way, and waived

the catering fee completely. And, then . . . Monica called her

lead corporate attorney, the senior partner of Lynch, Cahn &

Dodge, and got the worst news of her life.

As rhe pboiie slammed into its cradle, all of Monica s systems

ratcheted to Red Alert. Iler chafed nerve endings relayed their

message, *'Torpedo Room reporting. Vrapon ready."

“Gut,” came the reply.

A woman of Wagnerian stature, Monica Tietze strode out of hur

mahogany-paneled office in search of the quarry. The final

countdown had begun. She crossed the executive secretaries’

enclave, passed the huge inverted triangle shelves that held the

firm’s prestigious awards, and marched into enemy territory,

where she would find her target.

Monica stormed into Ernst’s executive suite and surveyed the

area. He was not at his desk. She reached the door to his private

kitchen, grabbed the knob, and yanked it open. There, next to

the stove, stood Ernst, spoon in hand.

“Ya, Liebling?’’ he asked.

That was another tiling she hated. He called anything with

breasts Liebling.

Then, right between his baby blue Augen, she let him have it.

The words roared out in rapid fire as she headed straight for

Ernst with the possible intention of ramming him broadside.

“Vas ist mil Yolanda? Du makes business trouble for last time! I

close your office. Du have only kitchen for vork. No more

mistakes. No more. Du are cine Katastrophe! Ist this, or I quit! I

quit! No more, Ernst. Ist you or me. Vliich you vant? You tell

me, Emst, Du tell me, in eine hour—cine hour. Ernst,

understand?”

Ernst dropped his spoon. A slight man who preferred “old

country'” sty led clothing, Emst looked toward the seething mass

of rage, and timidly asked, “Yolanda?'

“Mein Gott! You idiot!” Working her neon yellow stilettos from

the hips, Monica whirled about, gave it full throttle, and headed

for open sea. Ernst watched the slamming door careen into its

frame, bounce open, and come to its final rest against the floor,

victim of a broken hinge.

The smell of burning turned Ernst’s attention back to the stove.

Gude’s Gourmet Tartar Sauce, Version #1, had boiled its way

free of confinement and run from the top of the stove to the top

of Ernst’s shoes. He studied the sauce’s course, from point of

origin to point of destination, while he wondered what Yolanda

could ever have done to upset his partner so.

Monica decided to blow off steam by taking a walk along the

quay. That would give Ernst his hour in which to decide

whether or not to stay out of the business and in the kitchen,

once and for all. She stood in front of the elevator, busy with

her own thoughts, silently reaffirming the brilliance of her

ultimatum.

“He never get out of this trap. He can’t run business vithout me.

He do as 1 say. He stay out of business und in kitchen or I quit

und the company, the money, even test kitchen, vill all be gone.

Vhy,” she assured herself, “he don’t know the company

structure from a can of peas. Vhat vould he do vithout me? Just

vhat vould he do vithout me?’’ Monica’s coral lips spread into a

smile she reserved for special occasions. “Vhy, he fall flat as

souffle,’’ she concluded.

fhe elevator door jerked half-way open and then jerked forward

to close again when Monica shoved a five-inch heel in its path.

Pitching her formidable body sideways and exerting a single,

great shove, she forced the door fully open. The elevator's

temporary inhabitants stared at her.

“1st nothing,” said Monica, readjusting her jacket’s shoulder

pads.

As he walked into the Kuchen Kitchen offices, the Captain

detected the scent of burnt Tartar Sauce, bringing him to the

conclusion that Ernst was having a problem. He entered the

co-owner’s office and noticed the test kitchen s door ajar, one

hinge hanging loose.

“Ernst, my friend, are you in some trouble?” he asked. Peering

into the spacious galley, the Captain saw Ernst, wet dish cloth

in hand, cleaning sauce from his shoelaces.

While they had both known the Captain for many years, Monica

was the one who had spc nt the most time with him. Ernst had

never so much as gotten to know the fellow's real name. “Nein,

mein Captain." he responded with a shrug. “1st only Monica.

She ist angry' again."

The Captain fully reviewed the scene with its broken door.

messy7 stove, and ruined wing tips. “And what might have been

the cause of this anger?”

Tartar-stained wash cloth in hand, Ernst pointed to a cha«r

beside the art deco dining table, inviting his guest to sit down.

“Oh, ist only something mit Yolanda Baccus. I know not vhat

vas. Maybe bad vords.”

‘ Bad words?" asked the Captain, sitting down. “From Yolanda?

lliese words you refer to must have been potent indeed. The

Yolanda Baccus I am acquainted with is a most unlikely source

for such words. Should this be true, why is it Monica would

take you to task for such a thing?”

“I know not," said Ernst sadly shaking his head. “Monica und

me, ve have some problem, maybe."

“Well, my dear Ernst, prior to solving your problem, we must

be certain that we are solving the correct one. In these

instances, it’s always best to begin with Defining the Problem

Questions. Do you feel up to answering some questions in order

to solve this problem?"

“Ya, sure," came the weary answer.

“What do you think Yolanda might have done to upset Monica

so?"

“1 know not."

“Well, what was the last item you and Yolanda spoke about?"

“Ein parly for das office. Ein party. AuchV' Ernst slapped the

side of his face with the dirty cloth. “Ein party for—lor today!

Das I have forget!

“1 assume you and Monica were to attend it."

“Nein, nein. ve vas to kater."

Feeling that perhaps this problem could be readily solved, the

Captain’s hazel eyes studied Ernst from across the ornate table.

‘ Then this is what you forgot and what therefore caused

today’s exercise in target practice?"

“Vas no practice, mein Captain. Monica just say, she vant take

my office avay und give me only kitchen for vork. She say I go

from business or she go. In cine hour I tell her vas I do!"

Realizing now that defining this problem was going to take

longer than expected, (lie Captain pulled a little notepad and

pen from his shirt pocket. “My friend, an ultimatum is merely a

reflection of a problem; it is not the problem itself. Perhaps we

should continue.”

* ... ..... ’ ’

i a, sure.

“Wonderful. Now then, what do you feel might occur should

you simply ignore the problem?”

“1st no one vhat ignore Monica, Captain,” said Ernst.

“Quite right,” responded the Captain. “When did the problem

between you and Monica first appear?”

“America,” said Ernst. “She vanted come, so ve came. She

vanted run business, she run business. I cook. She go ein vay, I

go ein other.”

The Captain wrote down Ernst’s answer and then asked, “What

do you believe is the cause of this problem?”

“Ve no talk.”

“Why has this problem continued unsolved?”

“Ve no speak long time, und so, ve no can speak. 1st something

vas happens mit people.”

"Ernst, by assuming that change is impossible, you therefore

assume that nothing is possible. And not communicating isn’t

the problem. Merely a symptom of it.” The Captain continued,

“Do you really want to solve this problem? What if you simply

left instead?”

‘ Auch, nein Captain! Monica, she ist all to me.”

“What other things have changed in your relationship with

Monica?”

Ernst looked around the kitchen. “In Germany,” he answered,

“ve go dancing, ve in love, ve vant to marry . But business,

alvays business. So ve think later, maybe, later. But now ist too

late.”

‘ Look at tills from Monica’s point of view for a moment. What

might she be thinking?”

“Ya, Ya. She hates me. I alvays in vay of business. Business she

loves.”

“Have you ever asked Monica about this?”

‘ Nein.”

“What do you suppose you have done to add to this problem?"

“I cook, I travel, I not vith her much.”

“Ernst, if this problem is not resolved, what is it you fear losing

the most?”

“Oh . . . Monica!”

“And, what might occur should you attempt to speak with

Monica about this apparent problem?”

He cast his eyes toward the ceiling and answered, “I know

not.”

“Might you possibly consider this current situation to be an

opportunity to speak with her?”

Ernst looked down at the table, watching his finger draw circles

on ihe polished granite Finally, he said, "Maybe ve talk of this

. . . und then, maybe ve talk of other things.”

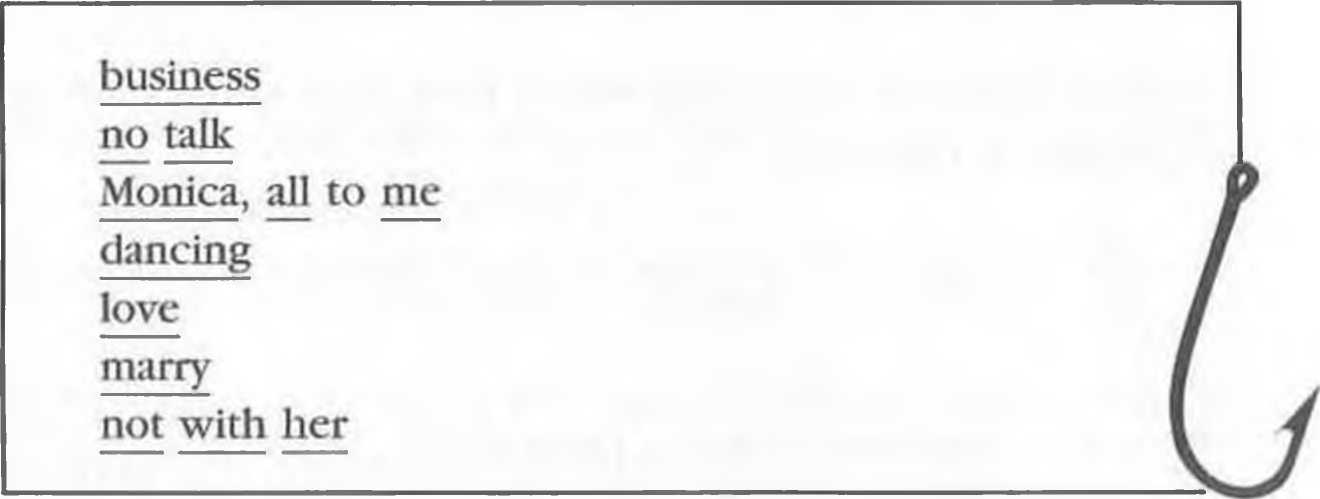

Allowing Ernst to begin to fully appreciate his own insights, the

Captain quietly studied his notes for a moment, underlining the

Word Bait:

The Captain gently tapped the table with his fingers. “Well, I

have an idea. What type of flower does Monica prefer above any

other?”

“Magnolia.”

Quickly writing in his notepad, the Captain said. “Then, my

friend, I suggest you immediately go to the flower shop

downstairs and get her a vase quite full of them.” He tore out

the page, handed it to Ernst and said, “Write this on the card.

Mind you, it will not be the solution in and of itself, merely a

step in the right direction.”

Ernst read the note and smiled. “Ya, Captain! Now, I see vhat

real problem ist!”

Monica worked her way back along the quay lined with fish

stores and restaurants. She entered Cannery Village’s courtyard

and immediately spotted the Captain standing alongside (he

fountain.

“My dearest Monica,” the Captain called out. ‘ Might 1 have but

a moment of your time?”

The Captain had given her considerable advice in the growth of

Kuchen Kitchens; at the very least she owed him the courtesy

of a response. “Ya, sure, Captain.”

As she approached he added, “1 understand that you and Ernst

might wish some assistance in solving a problem.”

Now just steps away, she asked, “Vhat, Captain?” In general,

Monica had come to believe that her partner had the attention

span of a ferret. For Ernst to discuss any situation with the

Captain, he must have finally located some facsimile of a

backbone. If nothing else, her lawyer would want to hear this.

He extended his hand in greeting. “What was it that I might

assist you with?”

“Ya, Ya. Captain,” conceded Monica, accepting his handshake.

“Ve have problems always mit business.”

“A few moments ago, Ernst allowed me to ask him some

questions to help discover what the real problem is. We came

to the conclusion chat it isn't Yolanda’s groundbreaking

ceremony, it isn’t his occasional straying into the company’s

business activities, and it isn't the ultimatum you gave him. In

fact, we came to quite another realization altogether.”

Monica was intrigued. “Ya?”

“Perhaps utilizing the same process, you and I might arrive at

(he very conclusion that Ernst and I did. Shall we give it a try?”

Curiosity was gelling the best of her. She warily agreed.

So the Captain began to ask Monica some of the same questions

he had asked Ernst. “If this problem should not be resolved,

what: is it you might lose?’’

Having convinced herself that it could never happen, Monica

mechanically answered. “Das company.’’

“Perhaps the added urgency to this matter might affect the

quality of a decision. Might there be any goodness in delaying

this impending confrontation?”

“Nein. Captain. Ist time now.”

4 Monica,” urged the Captain, “what other problems might be

associated with the present one?”

Hearing the sincerity in his voice, she looked up at him. “Ist

forty years, mein Captain. Ist forty years too late.”

“Monica,” he said softly. “What is the worst thing that can

happen should this problem not be resolved?”

i he thought of Ernst surfaced immediately.

As if he had read her mind, the Captain softly said, “Monica. 1

feel perhaps the three of us have discovered the real problem.

You and Ernst have simply forgotten you love one another.”

“Ernst loves his kitchen,” snapped Monica. “I must go now.”

She said a hasty good bye and headed across (he courtyard.

Monica entered her office and came to a full stop. There, atop

her desk, sat a huge crystal vase filled with (he biggest and most

magnificent magnolias she had even seen. Shu gasped, and

hurried over to them. There was an envelope. It was addressed

to Miss Tietze. She plucked it out and opened it. The card inside

read, “Monica, would you be so kind to attend the dance with

me on Saturday?” It was signed, “Love, Ernst.”

“Ya, liebling?” came the timid voice from behind her. Monica’s

eyes began to fill with tears. She turned and saw Ernst—in his

stocking feet.

“Ya, liebling!”

It’s amazing how many people go about trying to solve a

problem without first clarifying exactly what the problem is.

Sure, they have some idea about it, in a broad, general way.

Perhaps they want to come up with a new packaging design,

solve world hunger, write a book, or get into the film business.

Usually, they try to solve the problem like (his:

“I’ll just think about it and figure it out.”

“1 know! I'll bounce this off some of my friends.”

‘ Maybe a walk on the beach would help.”

They then proceed to think-think-think, hold a meeting, or put

the project off until next year. Sound familiar? Or, how about

this? When trying to solve a problem, do you doodle? Pace

around? Gaze at the ceiling, or even a little higher for divine

guidance? Clench your fists? Your teeth? How far does any of

that really get you?

The truth of the matter is that until you specifically define your

problem, both you and your pencil will be going around in

circles.

To define a problem, you need to ask yourself some specific

questions . . . Defining the Problem Questions. That’s how the

Captain helped Ernst and Monica. By asking questions, he

forced them to clarify the real problem . . . not just its

symptoms.

Clearly defining your problem is a matter of zeroing in on the

heart of it, progressively narrowing your focus until you have

pared it down into manageable proportions. The more

nebulous a problem seems, the more critical this step is.

Say you want to write a book. Good! What kind of book? Is it

going to be fiction, nonfiction, biography, autobiography,

textbook, or poetry? Will it be set in the past, present, or future?

Does it deal with business, science, health, cooking, travel, art,

or the circus? The more clearly you can state the problem, the

better.

For another example, suppose you want to create a new

packaging design. You could spend a great deal of time thinking

about all kinds of designs. You could travel the world studying

different packaging designs and still arrive home without any

answers, just because you haven't defined the problem.

You need to be more specific. So, what if you changed the

problem from “new packaging design" to "new packaging

design for food?" Better get your frequent ilyer vouchers out. . .

it’ll be another long trip. How about new packaging design for

tacos? Well, would it he for fish, chicken, or beef tacos? The

design would differ dramatically lor each.

If you reply “new packaging design for fish tacos,” you’ve

clearly established what the problem is simply by answering

questions that narrowed your focus. And look how these

questions have changed the words packaging and design into

real Word Bait!

See how’ the right questions helped an entrepreneur expand his

business:

Rick Raymond teaches at New York University and is the

president of his own environmental consulting company,

Richard Raymond Associates, Inc., in New York City. He

wanted to develop a new training program, but what type? By

working with Defining the Problem Questions Rick created the

new workshop, “Corporate Environmental Awareness Train-

ing.” “The questions helped me prepare a two-page synopsis

and a five-page description of the workshop; in essence a

business plan without the numbers attached,” says Rick.

The most difficult part of solving a problem is often how to

begin solving it. Defining the Problem Questions will sene as

icebreakers, helping you see just where to begin.

Sometimes you won’t know what the actual problem is until

you sec its solution. Other times, midway, you'll discover you

should have taken a different track, But you obviously must start

somewhere, and the following Defining the Problem Questions

are designed for just that purpose.

•

Think about a problem you’re currently trying to solve. Perhaps

you need to develop a new product, discover additional

applications for an existing product, create a packaging design,

generate variations on a story theme, seek a scientific

breakthrough, troubleshoot a problem, invent a process, design

a new machine, or plan an advertising campaign. To clearly

define your problem, read through the following questions.

Take 30 minutes to jot down your answers on a piece of

paper—your Bait Bucket. You needn’t try to answer all the

questions, because each one doesn’t apply to the same type of

problem. After the first question (it’s the most important for

everyone), you should choose only those that directly^ apply.

Underline the Word Bait in your answers and spend another 15

minutes fishing for your Catch—the solution to your problem.

1. What are you trying to accomplish? Consider:

What is the problem? What is the challenge?

What must be decided?

2. What if you were simply to ignore the situation? Might time

alone solve the problem?

3. If it won’t go away by itself*, is the problem really worth

solving?

Who agrees that this is an important challenge, and why?

Which relevant persons regard it as unimportant, and why?

By solving the problem, what do you stand to gain?

What do others stand to lose?

What is the worst that can happen if the problem is not

resolved?

4. What resources can you dedicate to reaching a solution?

5. How should decisions along the way to a solution be

reached?

Who should be involved in arriving at decisions?

Who should make the final decision?

In what manner should decisions be made (such as

unilaterally, by majority vote, by consensus)?

6. How will you know when you have achieved your

purpose? What are your criteria for success? For example:

What will people be doing well? How will they feel about

their work? How will they be getting along with each

other?

How will your own work be easier or more enjoyable?

What will you no longer have to attend to? What will you

no longer be concerned about?

7. Regarding your own interest in the matter, what are your

personal and professional reasons for working on this

project?

What risks or threats must you face in solving this problem?

What is most fearsome or threatening about the problem

itself?

8. How strong is your personal commitment to the effort? Are

you willing to invest the necessary time and energy?

Might you be overstimulated or too motivated to reach a

conclusion? How might this urgency affect the quality or

ethics of your decision?-

9. Whose problem is it?

Is it really your problem? What if you transfer responsibil-

ity?

10. When was the need or trouble first noticed? Did it occur

suddenly, or had it been developing for some time before

anyone noticed it?

How did it manifest itself? What were the symptoms or

indicators that something needed attention?

11. How did you become aware of the situation?

When did you become aware of it? How do you feel about

the liming, or about the way you were informed?

What else do you know about the history' of the problem?

12. What do you now understand about the cause or causes of

the problem?

13. Why hasn’t the problem already been solved?

14. What is the crux of the issue? To gain other perspectives so

you don’t solve the wrong problem:

Who can give you a different perspective on the nature of

the problem and the crux of the issue?

Whose point of view should be considered because the

person is directly affected by the problem?

What if you also get the perspective of at least one person

who appreciates the problem but who is not directly

affected by it?

What if you make believe that you are several different

people, viewing the same set of facts from various

perspectives (with different vested interests)?

15. What do you believe is the extent of the problem? (How

pervasive or widespread is it? What is its magnitude in

numbers?)

How quickly is the problem spreading or developing? What

is the risk of time passing without resolution?

What if you seek a temporary solution before a permanent

one?

Who can give you an unbiased perspective on the

magnitude or seriousness of the problem? (Perhaps

someone who has faced a similar challenge, or someone

outside your domain.)

16. How complex is the problem? What other problems are

linked with this one? How are thev interrelated? For

example:

How does one problem lead to—or result from—another?

What small problems add up to this big problem or make it

worse?

17. If you’re not fully aware of the assumptions guiding your

work, why continue wearing blinders? Consider:

Are you aiming at the right target? Are you working on the

right problem?

Have you oversimplified the problem?

What are you taking for granted about the urgency of a

solution? What if you just wait and see what happens?

What do you assume are the givens that can’t be changed?

What if you change them any way?

What are you assuming to be impossible? What if you tty it

nevertheless?

What procedures do you assume are necessary? What if you

skip them?

What “facts” have you assumed to be correct: How might

the information fool you?

What trouble can you redefine as an opportunity?

18. Have any of your answers to these questions changed your

thinking about the subject?

How has the challenge grown or expanded? What does it

now encompass?

Do you now see it as one problem, or as several interrelated

problems or sub-problems?

What do you now think is the root cause of the problem, or

what causes appear to be intermeshed?

What do you now believe is the crux of the issue?

Whose problem is it now? If it’s not yours now, why stay

involved?

Considering the big picture, what about this problem is

most important?

What is the most difficult barrier to a satisfying solution?

What is now your primary aim/goal/objective?

What about the problem is most urgent, or most in need of

immediate attention?

19. How do these changes in your thinking affect the decisions

that must be made?

How do the changes in your thinking affect the manner in

which decisions should be reached?

20. How confident are you that you have framed the central

problem, racher than a side issue or a false problem? (What

is your level of confidence, such as “95 percent sure'?)

How likely is it that the real problem will not be known

until you have reached at least a partial solution?

21. What are your thoughts about a final deadline for reaching

a satisfying conclusion?

22. Did your definition of the problem drastically change? If so,

return to the beginning of these questions and answer them

again with your new perspective in mind.

23- Who else is engaged in trying to solve this problem?

Who else should be involved? (What other groups,

agencies, and individuals share your interest? Why should

they participate?)

How can you enlist their participation?

Who is involved but should not be? Why is their

participation not relevant or not helpful?

Are any who are trying to solve this problem actually

making it worse? (In what way? What happens?)

How can you change the efforts that are not appropriate or

not helpful (as by remedial instruction, reassignment,

removal from the project, or asking the people what they

think)?

24. Whose attitude or behavior is the problem or part of the

problem?

What have other people done to perpetuate the situation?

(Who has done what, or failed to do what, and for what

reason?)

What have you done to perpetuate the situation?

25. Who has a vested interest in the status quo? How do they

benefit from things as they are—and what do they think

they’ll lose if the problem is solved?

Are those with a vested interest actually part of the

problem?

How likely is it that those with a vested interest will resist

your efforts? What form might their resistance take?

What thought have you given to coping with the

sell-protective behavior of those who wish to maintain the

status quo?

What thought have you given to mutual problem solving?

26. If the issue involves conflict between personal value

systems, how are emotions interfering with efforts to find a

solution?

27. What other emotions are interfering? For example:

What negative emotions—such as anger, envy, resentment,

mistrust, wounded pride, or protection of territory/turf—

are affecting the attitudes of those whose help you need?

How are the feelings expressed in people’s behavior?

What positive attitudes might also be interfering (such as

conscientiousness or extreme loyalty to company/col-

leagues)?

How are the attitudes expressed in people’s behavior?

How important is it to deal with the positive and negative

feelings before you forge ahead? What thought have you

given to the way this might be done?

28. If this is primarily a “people problem,” or if someone's

“misconduct” is of central concern, what is the nature of

the behavior, and who is engaged in it?

To whom is the behavior objectionable, and for what

reason?

What appears to be the purpose of the “misconduct”? (To

gain attention? To win a power struggle? To seek revenge?)

To check your analysis: How does the recipient of this

behavior feel when the person behaves this way? (Irritated?

Challenged? Defeated? Hurt?)

What other payoffs does the “perpetrator” gain from this

behavior?

What do you think the person is trying to say about himself

or herscif by engaging in this conduct (such as I’m

powerful . . . I’m brave . . . I’m smarter than you . . . I'm

important ... I need help)?

29. Who else do you think may be contributing to the behavior

by egging it on or approving of it?

What satisfaction or reward do those in the background

gain by tolerating or contributing to the “misconduct”?

30. What efforts have been made to stop or modify' the

behavior? (Who has done what with whom?)

How does the person respond to your efforts to stop the

behavior?

What happens when you steadfastly ignore it?

What happens when you allow logical consequences to

lake (heir course (such as allowing the person to

experience failure, rather than rescuing or covering for the

person)?

As a quick reference guide for your convenience, a listing of

these task-specific questions, along with those from other

chapters of The UteaFisber, is included in Part 4: Fishing Tackle.

Some folks go fishing for lots of reasons:

When they needed to select a new Musical Director, Pastor

Graeme Rosenau of Mount Olive Lutheran Church in La Mirada,

California, went angling before presenting the problem to his

special committee. According to Pastor Rosenau, “By going

through the Defining the Problem Questions, I was able to

develop a concise new job description that the committee

considered a major improvement over the old one.” The pastor

also uses this process to develop ideas for sermons, articles,

classes, and retreats.